The Unemployment Conspiracy

** This article was published on Counterpunch December 28, 2017 **

Real unemployment in the U.S. today hovers around 8.3%, afflicting more than 17 million people. This is roughly equivalent to the combined populations of New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago and Houston. Over one third of the working age population has given up looking for work.

Real unemployment in the U.S. today hovers around 8.3%, afflicting more than 17 million people. This is roughly equivalent to the combined populations of New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago and Houston. Over one third of the working age population has given up looking for work.

On

top of this, pundits project

that many more jobs will be lost to automation in the near future, with

computers and robots replacing as many as 49% of the jobs now done by humans. The

mechanization of dirty, dangerous, repetitive, mind-numbing tasks should be a

blessing. Instead, the future is described in apocalyptic terms. Why?

The

problem is rooted in the disingenuous narrative we are fed. Jobs, so the story

goes, are mysterious, ephemeral things, whose comings and goings are largely

beyond our control. The number of available jobs has to vary independently from

the work that needs to be done and the number of people available to do it, or

so we are told.

There

is plenty of work that needs to be done –converting our energy industry to

renewables, repairing and enhancing infrastructure, building housing for all

who need it, improving student-teacher ratios, increasing healthcare and

eldercare staff, and so much more. And there are millions looking for useful

work. The disconnect between people wanting to work, work that needs to be done

and the number of jobs that happen to be available only occurs if the guiding

principle for job availability is profit.

But when the needs of society as a whole are prioritized over the needs of

wealthy few at the top, then achieving permanent, full employment is a piece of

cake.

Productivity at Our Service

Today,

the putative standard is a forty-hour workweek, with a concomitant eight-hour

day. But for more than half of U.S. history, the workweek was longer. Not until

1898 did mineworkers win the eight-hour day. Two years later, the movement for

a shorter workweek spread to the San Francisco Building Trades. By 1905, the

eight-hour day was established coast-to-coast in the printing trades. The Ford

Motor Company adopted the new shorter workweek in 1914. Railroad workers won

the right in 1916. Only in 1937, with the adoption of the Fair Labor Standards

Act, did the eight-hour day become the national standard. (While many today are

compelled to work longer in order to make ends meet, the legal norm remains 40

hours.)

But

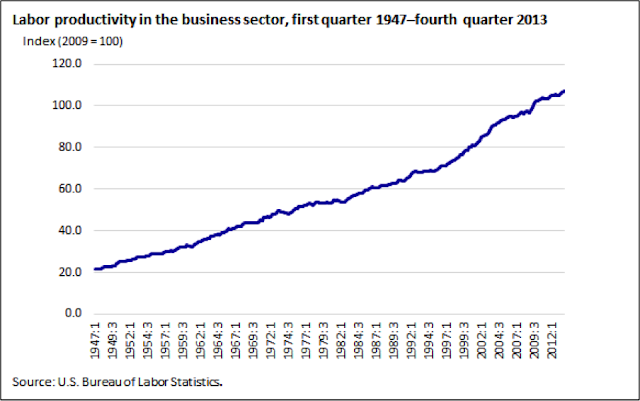

since 1937, the productivity of American labor has increased more than

six-fold! In other words, the value produced by a full day’s labor in 1937

would require less than two hours today.

So

an obvious solution to unemployment presents itself: reduce the workweek with no

reduction in pay.

If

the workweek were reduced from 40 to 30 hours, it would create 53 million new

jobs[1].

This is more than three times the current number of unemployed. To fill all the

remaining slots and maintain current production levels, we would have to plead

with the governments of Mexico, Central America and elsewhere to send more immigrants

our way!

Can

we afford this? Absolutely. Up to now – and especially since 1973 – increases

in productivity have been siphoned off as corporate profits and enriched only those

at the top.

Implementing 30 hours work for 40 hours pay (“30-for-40”) would simply redirect newly produced wealth away from corporate profits and back into the pockets of those who produce it. Instead of all the benefits of automation and increased productivity going to the top 1%, 30-for-40 would allocate a greater share of those gains to working people.

Implementing 30 hours work for 40 hours pay (“30-for-40”) would simply redirect newly produced wealth away from corporate profits and back into the pockets of those who produce it. Instead of all the benefits of automation and increased productivity going to the top 1%, 30-for-40 would allocate a greater share of those gains to working people.

Big Business Despises Full Employment

Not

only would using 30-for-40 to eliminate unemployment directly cut into

corporate profits, there are other side effects that corporate behemoths hate but

working people would love.

To

begin with, full employment would strengthen the working class vis-à-vis the

1%. With abundant, well-paying jobs for all, there would be no one a

recalcitrant company could hire as strikebreakers if the workers organized to

withhold their labor. It would be more difficult to harass and victimize union

organizers because, with full employment, all workers would be harder to

replace.

What’s

more, less time at work leaves more time for other things. This would include

time for rest, recreation, attention to family and exploring creative

endeavors. But it would also allow extra time for education, organizing,

getting involved and fighting back. In a world imbalanced by massive economic,

social and political inequality, allowing the majority more time for education

and organization is the last thing those at the top want to see.

Jobs For All vs. Universal Basic Income

Of

course, basic human solidarity demands that anyone who is old, sick, disabled

or otherwise unable to work should be provided for at society’s expense, with

their medical care fully covered and living expenses provided at union wage

scales. This can easily be paid for by reallocating funds from the oppressive

military budget and by taxing corporate profits. This policy should be combined

with a guarantee of a job for all who are able to work.

Lately,

some have promoted the notion of a Universal Basic Income (UBI). To the extent

that a UBI were funded by redistributing wealth from those at the top to those

below – a principle that is by no means guaranteed by the concept – a UBI could

be a positive reform. But a UBI is no substitute for a guarantee of jobs for

all. Why not?

First

and foremost, labor is power. The only power that can counter the concentrated

riches of the ruling oligarchs is the collective organization of millions of

every-day working people, who, as it happens, produce all of society’s wealth. The

root of working class power is the fact that the labor of millions of people

generates the riches enjoyed by those at the top, as well as the considerably

smaller share currently allocated to the majority. By withholding their labor

en mass, working people have ultimate veto power over any government policy. Guaranteeing

jobs for all strengthens the ties of working people to production, maximizing

the number participating in the labor force and, thus, the number who have a

hand on the lever of society’s productive apparatus. A UBI by itself, by contrast,

does nothing to reinforce people’s connection to work – that is, to the fundamental

engine of wealth creation.

In

addition, the rate of any UBI will necessarily be too low. There is a built-in imperative

for a UBI to be small enough to encourage people to work. In order to induce

people to work at all, the UBI has to be inadequate (or “barely adequate”) to live on by itself. But in

the absence of guaranteed jobs for all, “encouraging people to work” means

compelling them to compete for an insufficient number of low paying positions.

When the supply of labor exceeds its demand in available jobs, wages are driven

down, all other things being equal. And if the UBI is to be low enough to

encourage people to work, it must ultimately follow wages downward. So,

contrary to the assertion of UBI boosters that it would exert upward pressure

on wages, a UBI without a job guarantee is just as likely to lead to a race to

the bottom.

A

UBI is also susceptible to other kinds of manipulation. If a UBI is used to justify cuts to Medicaid, food

stamps, unemployment compensation and other social programs, it’s all too easy

for the programs replaced to be inadequately covered by the UBI, or for some

sectors of the population to benefit at the expense of others.

A

UBI can be used to pit employed workers against those without jobs. And, a UBI would

do little to address conditions on the job or provide more than a palliative

remedy for the unjust distribution of gains from increased automation and

productivity.

A

job guarantee is different. It would establish a principle that strengthens the

hand of working people as a whole. And the concept of “jobs for all” is

automatically adjustable: As productivity or the relative size of the work

force increases, the workweek can be reduced from 30, to 25 or fewer hours to

spread the remaining work around. That’s what a rational society, freed from

profit-driven tyranny would do.

The

next time some pundit or politician tells you we can’t guarantee jobs for all, recognize

that they’re playing you for a chump. They’re drawing an artificial box and

counting on you not thinking outside it. Remind them that their assertion is only

true if profits are prioritized over human needs. Explain that 30-for-40 solves

the problem handily, at great benefit to the vast majority. And who knows? With

guaranteed jobs for all, even narrow-minded pundits and politicians might be

able to find socially useful work.

[1]

There are 160 million

workers today. (160 million * 40

hours) = (213.3 million * 30 hours),

with (213 million – 160 million) = 53 million. Or: (160 million * 38.7 hours) =

(215.7 million * 28.7 hours), with (215 million – 160 million) = 55 million.

Comments

Post a Comment